Learning about Tyrosinase Through Database Research

In good research, learning as much as possible about the system under investigation is important. The first place to look is journal articles that have been written by researchers. Links to critical search databases are found in the DePaul University Chemistry Research Guide (See Table 1). Through the research guide, you will find links to specialized journal databases such as SciFinder (most recommended), ISI Web Of Science, ScienceDirect, Biological Abstracts, or Academic Search Complete.

Additionally, protein and DNA sequences and structures have been assembled in databases. New databases are constantly being developed. Table 1 gives a list of some databases that are useful to find information about proteins. Address often change. If a link in this table does not work, you may find the resource by searching the name with your favorite search engine. Please notify the instructors via the Discussion Board so that we may update the link.

Table 1. Biochemical databases arranged from most to least used in this course

|

Name |

Description |

URL |

|

BRaunschweig ENzyme Database (BRENDA) |

Information about enzymes |

|

|

NCBI Protein |

Multi-database protein sequence searches (including GenBank, Swiss-Prot, and PDB) |

|

|

Protein Data Bank (PDB) |

Protein structures determined by X-ray or NMR |

|

|

DePaul Chemistry Research Guide |

Specialized search engines for searching journal collections (e.g. SciFinder) |

|

|

NCBI GQuery |

Search many databases simultaneously (genomic, proteomic, and systems biology) |

|

|

NCBI GenBank |

Multi-database nucleotide sequence searches |

|

|

NCBI PubMed |

Public journal database |

|

|

Swiss-protein |

Protein sequences and analysis |

|

|

Swiss-model |

Protein structure homology-modelling |

|

|

Protein Information Resource |

Database searching for proteins (genomic, proteomic and systems biology) |

|

|

Database list at Nucleic Acids Research |

The most comprehensive list of bioinformatics databases |

International Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC)

Currently, the principal source of protein sequences are computer-based translations of DNA sequences deposited in primary nucleotide sequence databases. These are GenBank, maintained by the U.S. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI); the DNA Databank of Japan (DDBJ); and the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) Nucleotide Sequence Database, maintained by the European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI). New DNA sequence data can be deposited with any of these three databases, which form an International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration (INSDC, http://insdc.org), and the data between the databases is shared and updated on a daily basis so that DNA sequences kept in each database are essentially identical. These DNA sequence databases are repositories for raw sequence data submitted directly from experiments and DNA-sequencing projects. The entries are heavily annotated, containing not only the DNA sequence itself but also literature references, putative start and stop codons for translation, and deduced protein sequence when appropriate.

Databases may be curated (reviewed for accuracy by humans) and uncurated (where people can add content at any time). The advantage of a curated database is the information can be viewed as correct at the time the material was reviewed. The disadvantage is the database is not current because of the time taken to review all information. The advantage of an uncuarated database is that information can be added as soon as it has been discovered. The disadvantage is that not all material will be accurate and upon review the data will be removed. A good review article about curated databases is found within the D2L site (curateddbs). Which databases are curated? Swiss-Prot, Protein Information Resource (PIR), Protein Data Bank (PDB), and Protein Research Foundation (PRF). Which databases are uncurated? GenBank and its international mirror databases (DDBJ and EMBL). When searching these sequence databases and retrieving sequence information, it is important to bear in mind that the sequences in the databases are in fact repositories for raw data and that the databases are not heavily curated. The submitter is responsible for the correctness of the sequence and its annotation, and further updates or corrections or both come from the submitter.

NCBI Protein Database

The NCBI Protein Database offers a complete set of all protein sequences deduced through DNA translations. NCBI Protein is a data is an integrated search-and-retrieval system that can be used to search all sequence databases at once with a single query string. In addition to uncurated translated protein sequences from GenBank/DDBJ/EMBL, the proteins in the Entrez system include sequences from curated protein sequence databases Swiss-Prot, Protein Information Resource (PIR), Protein Data Bank (PDB), and Protein Research Foundation (PRF). While this makes the NCBI Protein nearly complete, ensuring that almost any protein sequence information can be retrieved, the database is excessively large and redundant. For practical purposes, NCBI has also created a non-redundant database, in which identical protein sequences from the same organism appear as a single entry. In addition to the sequence information, each NCBI Protein entry has links to all databases maintained by the NCBI, such as GenBank (which retrieves the corresponding nucleotide sequence), PubMed, Taxonomy database, Molecular Modeling Database (contains three-dimensional structures of proteins and polynucleotides), and Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM, for proteins associated with human diseases).

When searching these sequence databases and retrieving sequence information, it is important to bear in mind that the sequences in the databases are in fact repositories for raw data and that the databases are not heavily curated. The submitter is responsible for the correctness of the sequence and its annotation, and further updates or corrections or both come from the submitter. Despite this, Entrez Proteins are currently the ultimate resource for almost any protein sequence.

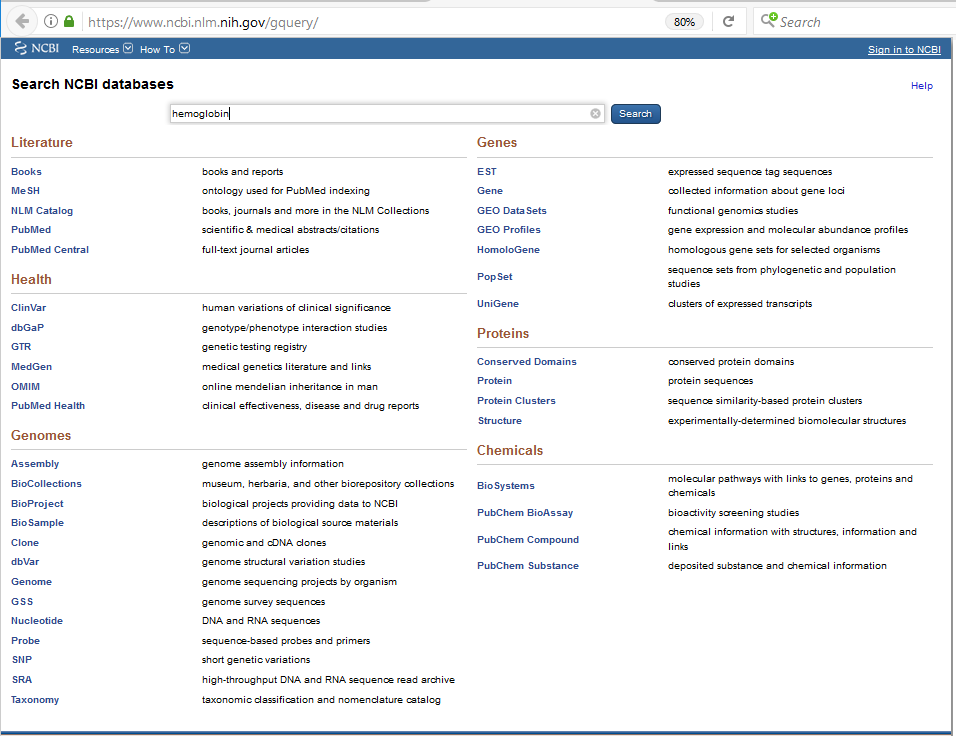

All NCBI databases may be searched through a browser called GQuery, it is an integrated search-and-retrieval tool that can be used to search all databases maintained by NCBI at once with a single query string.

Figure 1. The NCBI database list on the GQuery search page

UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB): Swiss-Prot and TrEMBL.

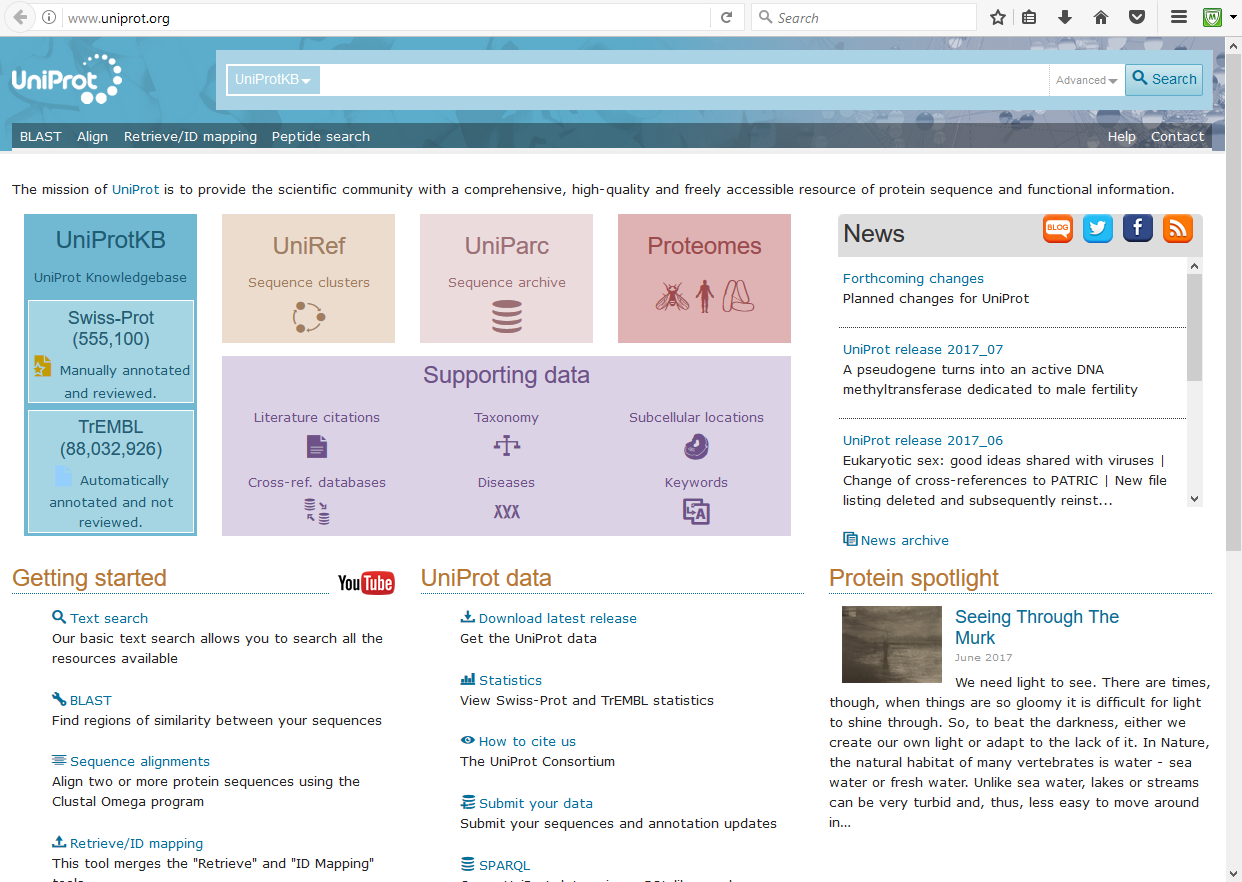

The UniProt Knowledgebase (UniProtKB) is the central hub for the collection of functional information on proteins. The core data mandatory for each UniProtKB entry includes the amino acid sequence, protein name or description, taxonomic data and citation information. UniProtKB contains two sections: the reviewed section (Swiss-Prot) and the unreviewed (TrEMBL).

In contrast to Entrez Proteins, Swiss-Prot is not just a repository for protein sequences but is a collection of confirmed protein sequences that is extensively annotated with information about protein structure and function, posttranslational modifications, isoenzyme variants, and bibliographic references. Swiss-Prot entries are linked to various external databases such as NCBI PubMed, the DNA sequence databases GenBank/DDBJ/EMBL, and protein sequence motifs and domain databases (PROSITE, Pfam and BLOCKS). The quality of the data in Swiss-Prot is very high because it is curated by human experts. New sequences are added into the database after analysis and verification by experts. Unfortunately, for this reason the coverage in Swiss-Prot is typically out-of-date by one or two years.

In order to speed up the entry of protein sequences into the Swiss-Prot, a supplemental database, TrEMBL, was developed. The sequences in the TrEMBL are translations of all coding sequences in the EMBL nucleotide sequence database, and each entry is in the Swiss-Prot format style, waiting for curation and entry into the Swiss-Prot. Since TrEMBL entries are generated automatically without curation by human experts, some proteins included in the database can be hypothetical, unlike the Swiss-Prot that contains only confirmed protein sequences. TrEMBL is considered to be less redundant than a general NCBI Protein search.

Even though the contents of UniProtKB are searchable on NCBI, it contains many unique useful visualization tools that are worth trying.

Figure 2. The UniProt home page

The Protein Databank (PDB)

While Swiss-Prot is a major database of confirmed protein sequences, the PDB is a repository for three-dimensional structures of proteins and nucleic acids. Since determination of the three-dimensional structure of a protein is very difficult when compared to primary sequence analysis, the number of entries in the PDB is even smaller than Swiss-Prot. As with Swiss-Prot, data in PDB are extensively curated and are of very high quality.

The Worldwide Protein Data Bank (PDB) is the primary repository for three-dimensional structural information about proteins, nucleic acids and complex assemblies. The structures are determined using X-ray crystallography, NMR, or electron microscopy. These techniques can be difficult to use with proteins due to the large size of the molecule, hard to obtain single crystals and solubility in solvents needed for NMR. For this reason the number of entries in the PDB is relatively small. The data in PDB are extensively curated and are of very high quality.

Figure 3. The PDB home page

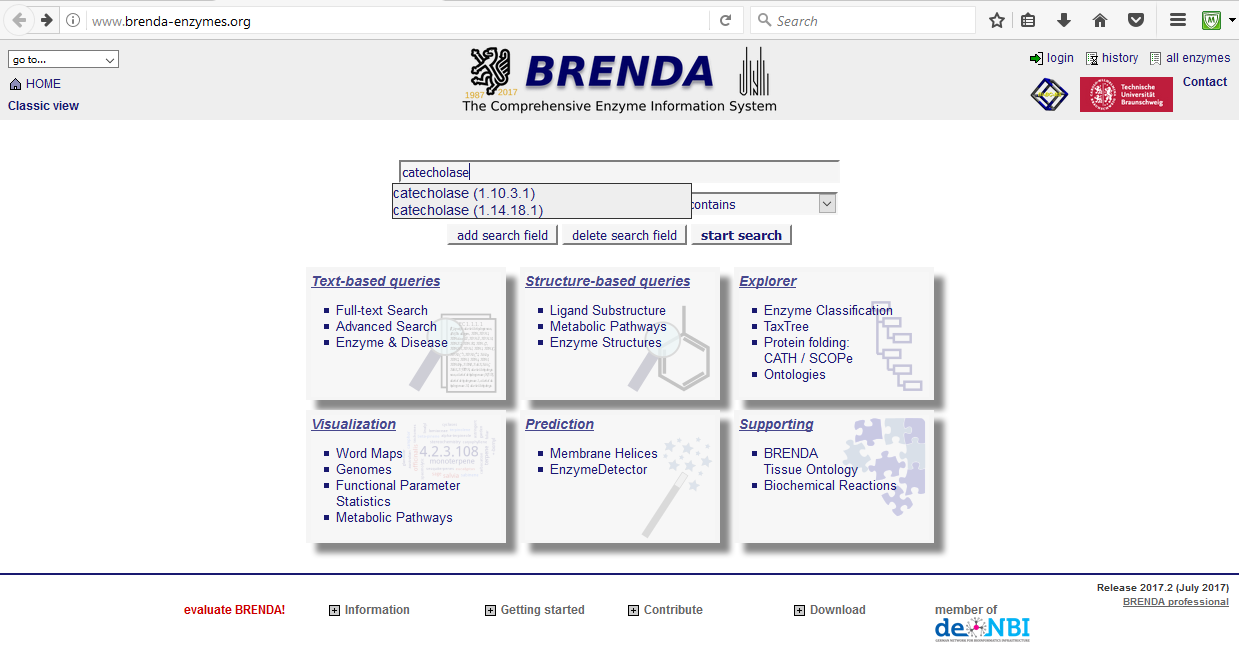

The BRaunschweig ENzyme Database (BRENDA)

BRENDA is a comprehensive curated database dedicated specifically to cataloging information about enzymes. BRENDA covers information about an enzyme's nomenclature, reaction and specificity, enzyme structure, isolation and preparation, enzyme stability, kinetic parameters, occurrence and localization, application of enzymes, and ligand-related data. The data originates from almost 85,000 different scientific articles. Each enzyme entry is clearly linked to at least one literature reference, to its source organism, and, where available, to the protein sequence of the enzyme. Furthermore, cross-references to external information resources such as sequence and 3D-structure databases are provided.

Unlike other proteins, enzymes specifically have a categorization system related to the type of reaction they catalyze. It is called the Enzyme Commision (EC) number (follow this link to see examples of what the numeric categories specify). EC numbers specify enzyme-catalyzed reactions, not enzymes themselves. Quite often, different enzymes from different organisms, with different folds, or even no evolutionary relatedness catalyze the same chemiscal reaction type and thus receive the same EC number. In contrast, the accessation number identifiers used in other protein databases such as NCBI Protein and PDB catalog a protein by its specific entry (thus there are redundancies) and UniProt specifies a protein by its amino acid sequence.

Figure 4. The BRENDA search page, notice search for catecholase resulted in more than one class of enzyme