The New Arts of Persuasion: Contemporary Media, Communications, and Rhetoric |

The New Arts of Persuasion: Contemporary Media, Communications, and Rhetoric |

Hesiod mentions a Peitho (Theogony, l. 349), whom he identifies only as one of the three thousand daughters of Ocean and Tethys. However, this Peitho appears to be an altogether different figure from the Peitho associated with beguiling eloquence and the power of rhetoric. Most of the standard classical encyclopedias and dictionaries of mythology are similarly equivocal and vague about her identity. In a few sources, she is identified not only as a personified Persuasion, but is also associated, like her Roman equivalent Suada, with Deception and Desire.

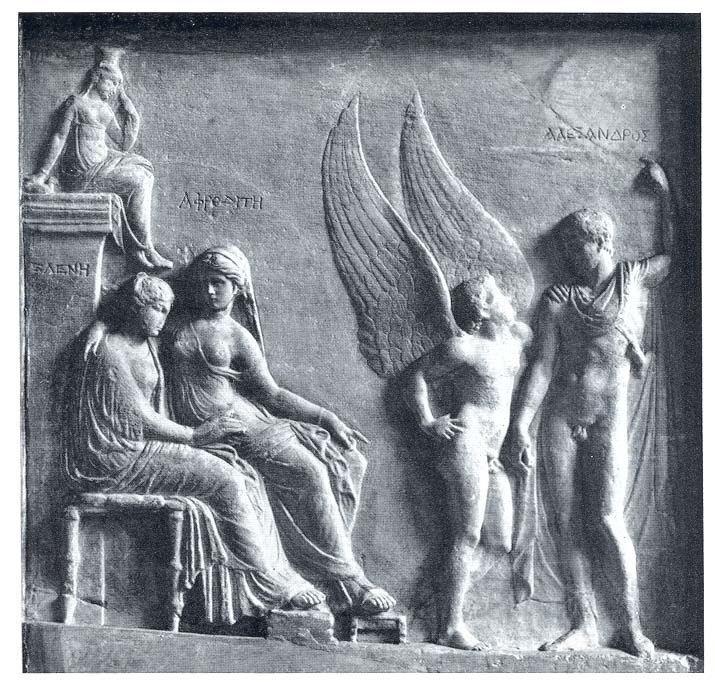

In a few scattered literary references and on numerous

Greek friezes and vases Peitho is typically depicted as an attendant in

the company of Eros and Aphrodite. In the image below, for example, she

sits pensively atop a column in the upper left background of a first century

relief--an indirect participant in an intriguing seduction scene. Seated

in the left foreground are Helen (of Fall of Troy fame) and Aphrodite;

to the right stand Eros and Paris.

Aphrodite has placed her arm around the seemingly shy (or artfully

coy) Helen, perhaps confiding to her young protege (as expert to talented

novice) some secret insight about the joys and rigors of forbidden love.

Meanwhile Eros and Paris are having their own tete-a-tete, with the winged

love-god apparently offering last-minute encouragement to the daring but

understandably anxious Trojan. But note: whatever Eros and Aphrodite appear

to be saying to the nervous couple (on the verge of the most notorious

Abduction/Elopement in all of literature), their words come ultimately

from Peitho. Consider, for example, the goddess's posture of extreme concentration

(much in the manner of Rodin's Le Penseur). It appears that she

is not merely guiding, but actually telepathically inspiring

the speeches that will shatter Helen's resistance and bolster Paris's

resolve. No wonder Helen and Paris run off together. Who can withstand

the combined forces of Persuasion and Love?

Effective persuasion, in other words, involves either

the direct satisfaction of a need or the artful manipulation (through "trigger"

words, alluring images, and other verbal or graphic stimuli) of latent

desires. A corollary insight to this principle is that you can't sell anything--a

candidate, a product, a proposal, an idea--until you make your audience

want it.

|

|

According to psychoanalysis and other influential schools of depth psychology, human behavior is irrationally driven. Our conscious decisions, Freud argued, are seldom the result of simple, rational processes but are always partly determined by primal appetites and passions. Even in the most mundane matters--from our entertainment choices to our grocery lists-- we are all to some degree governed by basic instincts and hidden desires.

Most of us readily acknowledge the power and usefulness of Freud's insights. However, to recognize that our behavior is strongly influenced by our subconscious is hardly to admit (as some psychologists, public relations pundits, and advertising experts seem to suppose) that we are completely at the mercy of our secret fantasies and buried prejudices, hence easy prey for the glib symbol-artist, word-spinner, or demogogue. Can consumers really be lured into purchasing a product by subtle massagings of the unconscious? Can voters--or coy maidens--be won over by smooth applications of brainwash or guileful subliminal appeals?

According to an increasingly popular and influential

school of human behavior known as

Rational

Choice Theory, the answer to such questions is no. Without denying

that our decisions are subject to irrational influences, adherents of this

theory (mainly philosophers and economists--from the Enlightenment to the

present) believe that by and large most of our behavior is the result

of deliberate choice. In other words, we perform actions, make purchases,

devise plans, etc., not absent-mindedly or by reflex, but pragmatically

and sytematically--through our best rational calculations of consequence

and self-interest. Peitho, according to this view, is most successful when

she presents valid, compelling arguments instead of resorting to cunning

deceptions or turning on her sexual charms.

Agree with it or not, Rational Choice Theory is a

subject of vital interest to communicators, with clear implications for

effective message design. Certainly no one interested in the arts of contemporary

persuasion can afford to be ignorant of it.

Suggested further reading:

AUBUCHON, NORBERT. The Anatomy of Persuasion. New York: Amacom,

1997.

AUSTEN, JANE. Persuasion.

BUXTON, R.G.A. Persuasion in Greek Tragedy: a Study of Peitho. Cambridge,

1982. MAYHEW, LEON H. The New Public: Professional Communication and

the Means of Social Influence. New York: Cambridge University Press,

1997.

MAZLOW, ABRAHAM H. Motivation and Personality, 3rd ed. New York:

HarperCollins, 1987.

SCHERER, MARGARET R. The Legends of Troy in Art and Literature.

London: Phaidon Press, 1963.