Peter Vandenberg An early version of this essay was written for the "Last Lecture" Series at DePaul University. The announcement for the series asks, "What would you say at your last public talk?" The story of my social and economic success, such as it is, is a story of inscription. My identity has become textualized, and this has been a process of editing, of validation and annulment. |

* * *

A couple

of years ago Karen and I moved into the main floor of a two-flat in Chicago’s

Old Irving Park neighborhood. It was not unlike a dozen other two-flats

we looked at, save one shimmering difference.

This one came with access to half of a two-car garage. When we signed

the lease, in addition to ultra-longlife lithium batteries for our

smoke detectors and two sets of keys, our new landlords handed us an

electronic garage-door opener. The sense of ceremony was palpable—for

the first time in our lives, we would be parking a car indoors! Just

a few minutes later we pulled away from the curb in front of the building,

rounded the corner into the alley and pulled up to the garage. I barely

lifted a finger, and with the press of a button the door rose and we

drove past our parents into the mythical middle class.

My father built the house I grew up in, but with six kids and a vita

that ended with a high school diploma, his garage never emerged from

the blueprints. I

grew up, like my older brothers, in love with cars. And the evidence of that

desire, absent an enclosure to organize it and mask it from public view, spread

out across the yard. I grew up rolling my pedal car around two old Dodges—a

1940 and a '48—and a modified '27 Ford with a DeSoto hemi that my brother

and his friends would pull to Cornhusker Raceway behind an old pick-up in the

early 1960s. The Vandenberg garage was a kind of present absence that eluded

us and provoked the neighbors, one of which eventually convinced the city to

officially declare the Dodges a public nuisance. Lacking a place to conceal

his desire, brother Bob sold them to the junkyard for $7.50 each. Later my

own cars and friends replaced my brothers', and I lived out the white-trash

tropes assigned to those who do their own maintenance in undesignated, unelectrified "natural" space.

I was a shade-tree mechanic by day, a flashlight mechanic by night.

I graduated from high school in the nation's bicentennial year, in the

aftermath of the Arab Oil Embargo, and much of that spring my 1968 Plymouth

Roadrunner coupe sat in the driveway. With help from my brother, my friend

George and I rebuilt the motor, and I paid for the  machine

work and parts a little each week with money I earned after school working

for Brother Bob. To reload the pistons, bolt in the new crank and cam,

and torque down the heads out of the dust, we carried the engine block

inside the house! That car—with no apologies for the pronunciation

we never questioned— "ran like a stripe-ed-assed ape."

But in the two years it was mine, it spent the night indoors just once—when

it was painted. Late that summer, with gasoline prices soaring, with college

starting and no college savings to draw on, I sold my $3,000 investment

for $1,150. The man who bought the car came to look at it with his freshly

licensed son. They wore matching jackets. Before the man lifted the hood

of my car, he took a pair of white garden gloves from the trunk of his

big four-door. These people had garage written all over them.

machine

work and parts a little each week with money I earned after school working

for Brother Bob. To reload the pistons, bolt in the new crank and cam,

and torque down the heads out of the dust, we carried the engine block

inside the house! That car—with no apologies for the pronunciation

we never questioned— "ran like a stripe-ed-assed ape."

But in the two years it was mine, it spent the night indoors just once—when

it was painted. Late that summer, with gasoline prices soaring, with college

starting and no college savings to draw on, I sold my $3,000 investment

for $1,150. The man who bought the car came to look at it with his freshly

licensed son. They wore matching jackets. Before the man lifted the hood

of my car, he took a pair of white garden gloves from the trunk of his

big four-door. These people had garage written all over them.

The practical need for clean, dry space to work on and protect a car has

lessened as the "objects" that define my world became increasingly

abstract. But the broad, socio-economic meanings of garage continued,

until recently, to define a gap or lack of necessary space. My encounter

with privileged literacies has taken me "inside"; the youngest

of six children, I am the first to earn a college degree, the only one

to earn an advanced degree. My starting annual salary at DePaul University

in 1993 was nearly twice what my father earned in the best economic year

of his life. I have "learned to write" in ways my mother and

father could not have imagined, and this high literacy has served as an

able vehicle for vertical class movement. Unlike my father I have purchased

more than one new car, flown on a plane not owned by the armed forces,

and traveled through Europe. The literacy industry has opened many doors

for me; two years ago, it finally opened the garage.

* * *

I

was born on April 23, 1958. According to Lutheran Hospital's Bedside

Gazette, "wet weather predominated . . . from the Rockies to

the Appalachians with violent storms lashing the central and southern

parts of the Midwest"; "Israelis spent the night dancing in

the streets to mark the tenth anniversary of the nation's independence";

"The Spanish born queen of the gypsies . . . . Mimi Rosetto stopped

responding to treatment for a kidney ailment . . . but continued puffing

her clay pipe and downing gulps of plum brandy until she lapsed into a

coma."

I

was born on April 23, 1958. According to Lutheran Hospital's Bedside

Gazette, "wet weather predominated . . . from the Rockies to

the Appalachians with violent storms lashing the central and southern

parts of the Midwest"; "Israelis spent the night dancing in

the streets to mark the tenth anniversary of the nation's independence";

"The Spanish born queen of the gypsies . . . . Mimi Rosetto stopped

responding to treatment for a kidney ailment . . . but continued puffing

her clay pipe and downing gulps of plum brandy until she lapsed into a

coma."

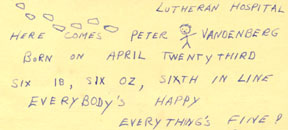

Easter, a holiday my family celebrated each year with both reverence and

great reverie, was apparently heavy on my mother's mind; from her hospital

bed she wrote me into the world like Peter Cottontail, on the back of

a two-cent postcard:

HERE COMES PETER VANDENBERG

BORN ON APRIL TWENTY THIRD

SIX LB, SIX OZ, SIXTH IN LINE

EVERYBODY'S HAPPY

EVERYTHING'S FINE! [Figure 3]

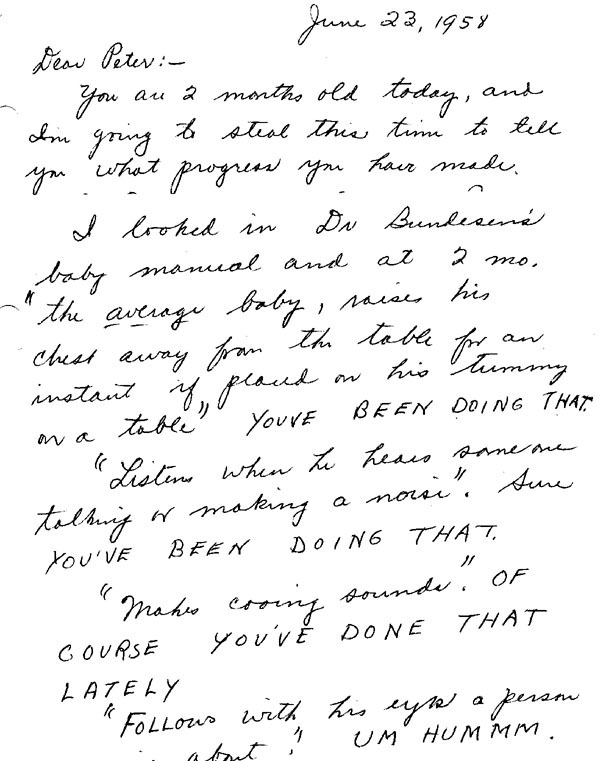

During my first two years, mom was in the occasional habit of writing me letters;

this one describes my first relationship of sorts with both a textbook and

standardized testing: June 23, 1958

Dear Peter:

You are two months old today, and I'm going to steal this time to tell

you what progress you have made. . . . Dr Bundesen's baby manual [says]

at 2

mos "the average baby raises his chest away from the table for an instant

if placed on his tummy on a table" YOU'VE BEEN DOING THAT.

"Listens when he hears someone talking or making a noise". Sure YOU'VE

BEEN DOING THAT.

"Makes cooing sounds." OF COURSE YOU'VE BEEN DOING THAT.

"Follows with his eyes a person moving about." UM HUMMM.

"Kicks his feet." EVEN BEFORE YOU WERE BORN!!!

"Makes pushing movements with his feet when held against a flat object"— Sure.

"A Baby at this age is playful [and] has tears when he cries (Just about

a wk ago I noticed the first tears). "Smiles"--There you had us stumped

but yesterday you did it, just under the deadline.

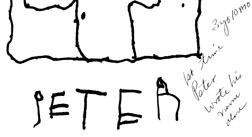

At

three years, ten months I wrote my name on my own for the first time,

and that winter addressed the envelope containing my letter to Santa Claus,

which was obviously never mailed! Our dining room table, overcrowded with

books and projects of one sort or another, was like a domestic writing

center. My father, who built the house on his own, except for the foundation

and chimney, as the story goes, designed bookcases for the walls of our

living room, and when I came along he was still making payments on a large

set of Encyclopedia Britannica that stretched under the length

of our living room window. Into another wall in the corner he built a

magazine rack, tall shelves with backs at an 80-degree angle and molding

along the front edge to keep periodicals from slipping off—just

like at the library. Each month during my grade-school years, copies of

Life, Look, Popular Mechanics, National

Geographic, Boys Life ,and Catholic Voice

were rotated off the wall rack and into stacks in the basement.

At

three years, ten months I wrote my name on my own for the first time,

and that winter addressed the envelope containing my letter to Santa Claus,

which was obviously never mailed! Our dining room table, overcrowded with

books and projects of one sort or another, was like a domestic writing

center. My father, who built the house on his own, except for the foundation

and chimney, as the story goes, designed bookcases for the walls of our

living room, and when I came along he was still making payments on a large

set of Encyclopedia Britannica that stretched under the length

of our living room window. Into another wall in the corner he built a

magazine rack, tall shelves with backs at an 80-degree angle and molding

along the front edge to keep periodicals from slipping off—just

like at the library. Each month during my grade-school years, copies of

Life, Look, Popular Mechanics, National

Geographic, Boys Life ,and Catholic Voice

were rotated off the wall rack and into stacks in the basement.

* * *

In

the fall of 1964, at Ashland Park Elementary, I authored the seminal

declarative sentence: "I can read and write." I

authored my first book, About Me and My Community, in the second grade;

it has seven chapters, including "My Home, "My School," "My

Church," and "My Store."

In

the fall of 1964, at Ashland Park Elementary, I authored the seminal

declarative sentence: "I can read and write." I

authored my first book, About Me and My Community, in the second grade;

it has seven chapters, including "My Home, "My School," "My

Church," and "My Store."

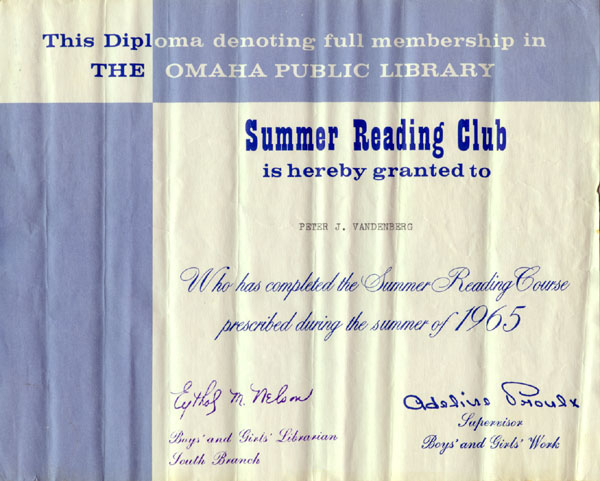

That summer I began riding the city bus from our house on 57th street

to the Public Library on 24th , in what we called South Omaha; my sister

Audrey, brother

Greg, and I were members of the Summer Reading Club. For me, riding

my bike or playing with my Tootsietoys along the dirt road in front of our

house was contingent on good standing as a reader.

I remember not wanting to go to grade school only once—when on

our way to the bus stop my sister and I saw my cat dead in the middle

of a busy Q street.

We called my Dad at work from the principle's office; he punched out

and came home to scoop up the cat and bury it in the yard so we wouldn't

see her when

we got off the bus. I loved grade school—it was a lot like home,

just more kids.

In the spring of third grade, my friendship with John Newcombe ended.

John lived just two blocks from me—the closest of my classmates—and

I loved going to his house as much as my mother tried to prevent me from

going. He had a bedroom of his own, and it was full of anything a kid

might want;

we played MouseTrap and Operation there, and when his older brother wasn't

home we could sneak into his room to admire the model cars he'd built,

which were keenly displayed on top of a mirror on his dresser so one

could appreciate

the detail of the undercarriages. I wanted a great many things in the

third grade, and most of them John Newcombe already had.

At some point that year, we were asked to read silently from a book,

beginning on the command, "Go." After a short while, Miss Scott

called "time" and

directed us to count up the number of words we had read. I don't remember now,

but I suspect we were in the process of determining which reading groups we

would end up in. I'm not sure if we were asked to call out our numbers in alphabetical

order, but I remember being proud to announce a very high one. And when I did,

John Newcombe turned wild. He jumped up out of his seat and in my direction

shouted "Liar!"; Miss Scott had to physically restrain him.

On another day, friendly once again, John and I traded a piece of paper

back and forth, trying to out do each other with forbidden vocabulary.

When my

Mom found the scrap in my pants pocket on laundry day, I took a pretty

healthy paddling despite a complete denial. Some years later, in an uncharacteristically

ironic moment about such things, Mom joked that she had given me an extra

whack

because some of the words were misspelled. John Newcombe and I went to

the

same schools for another nine years, but I don't remember ever speaking

to him after third grade. I was taking hold of reading and writing, and

as my

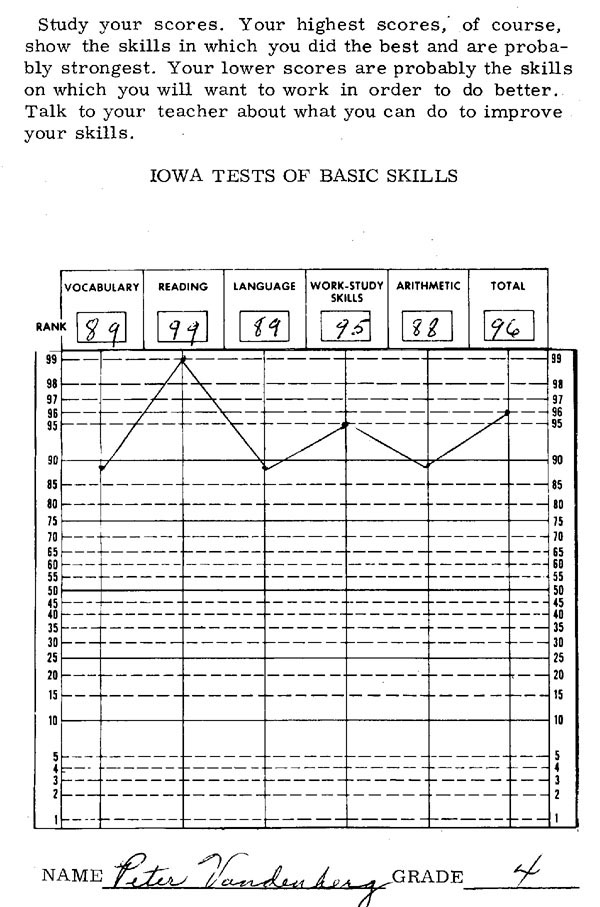

Iowa Basics Skills results show, reading and writing were taking hold

of me.

* * *

Two years ago, in a faculty seminar series, I read a paper about multiculturalism in composition studies. When I finished, my colleague, Lucy Rinehart, perhaps sensing some irony, asked me if I'd ever considered writing the paper outside the academic conventions that I was critiquing. I explained that I would need to publish the paper in the best journal I could, and I didn't think I had the ethos to work in a voice too personal. That summer, I earned a grant to support revision of that paper into an article manuscript, and thanks to a change of rules for summer stipends, then had to read the resulting paper at another faculty seminar series the following year! Lucy attended again, and, for her own reasons, I suppose, asked me almost exactly the same question. I gave her almost exactly the same answer. Lucy, this piece is a different answer.

* * *

In my sophomore honors English class, 1974, my friend Dale

and I—with the help of Dale's brother—wrote and produced a

13-minute 8mm film called "Land of the Unknown." The pilots

carrying the boys in Lord of the Flies, so our premise went,

were not swept out to see after all, but onto an adjacent island where

they were eventually eaten by Godzilla (thanks to several seconds of sci-fi

footage spliced into our film from a reel we bought at K-Mart). The teacher

was so impressed that Dale and I were asked to screen the movie for other

English classes, which meant we were excused from other subjects to do

so. It was my first encounter with research-based released time.

We tried to capture lightning in a bottle twice, using the school's video

equipment in a library study room for a docu-drama about the origins of

World War I. Drawing on a recently popular motion picture, we had graft-busting

New York City police detective Frank Serpico travel back in time to investigate

the assassination of Arch Duke Ferdinand. When Serpico's character engaged

in a tussle with another student playing a Serbian national whom Serpico

identified as a suspect, the two knocked a heavy wooden chair into the

wall, which summoned the librarian, who notified the teacher, who asked

us to roll the tape we had shot. Perhaps less interested in narrative

invention than faculty in English, the History teacher put a quick end

to the project.

My rise to power in journalism failed almost as quickly. As a sophomore

I applied to write sports for the school paper, and was assigned to cover

a football game as an audition of sorts. On the basis of that story, the

newspaper's faculty advisor made me Sports Editor, displacing a senior.

Within a few issues I had my own column, which the advisor insisted be

called "For Pete's Sake." During basketball season, the school's

principle, Dr John McQuinn, ordered a group of students to stop wearing

t-shirts emblazoned with the image of a jock strap and the words "Bryan

High Athletic Supporter." My next column was critical of the repression,

arguing that a school that had not won a single game for a three-year

stretch in the early 1970s should take "spirit" any way it could

get it. The principle killed the column; I invoked free speech and the

legacy of the school's namesake, William Jennings Bryan, but was turned

away. Though I continued to write high-school sports for a suburban newspaper,

The Bellevue Guide, through my senior year, I resigned from the

Bryan Orator.

I later ducked college preparatory English as a senior, signing up for

a course that was ranked as a 2 on a scale of 1-5 in difficulty. I remember

from that class the first line of A Tale of Two Cities, and I

remember giggling with my friend Dale (another underachiever) in the back

of the room as the 2's struggled to conjugate verbs and diagram English

constructions. For the next year we summed that class up with a sentence

that one of our classmates, no doubt with Herculean self-doubt, scratched

out on the board one day: "The bird did flew."

I smugly imagined, I think, that reading and writing continued to embrace me,

but already the ideological coherence between the primary discourse of my family

and that of the public institutions of schooling was beginning to weaken. The

boxes of memorabilia from which I've taken these images contain not a single

piece of graded work after junior high. My friends were beginning to talk about

college, and dorm life, and fraternities; I focused on my car. I must have

taken a college entrance examination, but I have no recollection of sitting

for it, much less studying for it. I don't remember making a choice to attend

the University of Nebraska at Omaha—it was that or nothing—and

I do remember using the term Loser to describe those who would not be going

to college. I don't remember my mother, the only one in a family of thirteen

to earn a high school diploma, ever saying anything at all to me about college.

The choice to go to UNO, for me, was strictly a matter of peer pressure. My

father, who told my mother that the Navy was a better option, offered one piece

of advice about university life. "Do what you're told over there," he

said.

I took six classes over the fall and spring semesters of 1976-77. My sociology

lecture met in a hall so big the professor wore a microphone clipped to his

jacket. Students filed in and out during the entire period. The experience

didn't seem like school to me, and I had no one to orient me to it. My sole

memory from that course was a teaching assistant requiring me to admit, in

front of my break-out study group, that I had stopped attending the weekly,

amplified lecture. I also took a course called "The New Testament" from

a man with a snow white beard who called the bible “an historical text.” We

fingered laminated maps of the Holy Land purchased at the school bookstore

as he lectured, pacing back and forth across the room, smiling and making eye

contact at times with each of us. Too timid to raise my hand in class, but

encouraged by his welcoming affect, I followed him down the hall one day afterward

and summoned him by name. He spun around and seemed to bear down on me; I sputtered

out something, and he came back like this: "Are you familiar with a concept

called 'office hours'?"

I took an A in just one course that year, Televison Production. My final

project was an early music video of sorts for the song, "Traveling

with the Rodeo." Two cameras were trained on easels bearing placards

to which various pictures of cowboys had been affixed. When the engineer

faded a camera out, I pulled down a placard to expose a new cowboy image—just

in time for the alternating camera to fade back in. I cut those cowboy

pictures from the stacks of magazines in my parents' basement and pasted

them onto construction paper—the same way I had constructed About

Me and My Community a lifetime earlier.

Back then, about 1965, my older brother Joe went AWOL from the Great Lakes

Navel Station, and the FBI came to our house to question my parents on his

whereabouts. Joe had already spent a year in the seminary at that point, and

said he had left both places because he couldn't find God in either one. Joe’s

two institutional departures devastated my parents, estranged him from the

family for the rest of my parents' lives, and served as warnings against the

most significant sort of transgression a Vandenberg might commit. I left college

in the spring of 1977 because I didn't understand what was happening there;

no one said a word about it. My parents’ working-class commitment to

reading and writing had carried me as far as it was going to into dominant-culture

institutions.

* * *

In the summer of 1981, half a dozen jobs past my first run at college, I was driving a concrete truck for a company in Kearney, Nebraska. On a particularly slow day, the dispatcher, who said everything through a fiercely flat mouth, told me to fire up an aging truck that would soon be sold at auction. “Old Number Three” sat at the end of the line, undriven for some time, a thin layer of cement dust shadowing the cab and mirrors. It would no doubt be purchased by a smaller, rural company in state, there was some interest in avoiding ill will by making sure it was in running order. I lugged out of the yard belching a widening column of blue-gray smoke from the stack. On the way to a housing subdivision north of town, eight yards of wet concrete churned slowly in the drum. Years later, I would watch the movie Titanic, learn how slowly the big ship reacted to evasive maneuvers, and recall Old Number Three. I braked, geared down, and turned off the street onto the job site, the muscle memory in my hands, arms, and legs treating this truck as if it were the other one, the one I'd been driving for a couple of years. The load, following its own momentum, refused the change in direction and pulled the right rear dualies off the ground. Steering into the tip already too late, I felt Old Number Three begin a slow roll to the driver's side. Like a third-class passenger I began climbing—toward the right-side door, which was slowly becoming the roof of the cab. Twenty tons of concrete pulled the back of the truck to the ground first, whipping the cab down flat beneath me. The impact pulled my hands off the passenger-side door rest, and I landed, standing inside the cab, without a scratch, my feet centered in what used to be the driver’s-side window. The fall somehow spiked the accelerator, and though the truck lay dead still on its side, the throttle was wide open. I bent down, turned off the key, and walked out the opening where the windshield used to be.

* * *

There's more to this story, but the official version would not be mine

to tell—call it simply “driver's error.” I spent the

next year or so working for a large, commercial construction company.

In addition to driving a dump truck and plowing snow from large commercial

lots and city streets, I put up metal buildings, laid pipe in unshorn

trenches, and worked as the fly-man on a pile driving crew.

Driving piles for a small, rural company is loud, dirty work. A big operation

backed by money and expertise will employ a solid, fixed-lead structure—a

scaffold-like apparatus that keeps the long, concrete pile safely vertical

as it is driven, something like the way an experienced carpenter firmly

grips a finish nail with thumb and forefinger. Operation is remote, meaning

that contact injury from the two-ton diesel hammer and/or a thirty-foot

concrete pile is unlikely. I was a fly-man on Carl Andresson’s crew,

though, and Carl had an aging Manitowoc lattice-boom crane that might

have been a sibling of that earnest but outmoded piece of equipment in

Mike Mulligan’s Steam Shovel. Carl dragged that crane all over Central

Nebraska and Northern Kansas behind a reeky cab-over Freightliner.

A swinging-lead pile operation is basically nothing more than an impact

hammer suspended from a single boom along with the pile; a fly-man is

the guy who guides the hammer onto the pile. Imagine an ink pen as the

pile and its cap as the hammer, each of them hanging on separate strings;

the fly-man, swinging between them from a third string, puts the cap on.

At a height equal with the top of the pile—30 feet or more depending

on the structure—the fly-man, pile, and hammer all dangle from a

single boom!

With a chain wrapped around it near the top, the pile is hoisted into

place and held almost upright by the crane operator, who also lowers the

hammer within a few feet of the pile. The hammer is driven down with such

naked force that without something to absorb the shock, the concrete pile

will splinter into pieces before it is fully absorbed by the ground. Today,

in most places, the top of the concrete pile is protected from the hardened

steel strike plate of the hammer by fitted cushions appropriately figured

as “helmets,” which are fitted snugly over the top of the

pile. Carl Andersson had likely never heard of pile helmets; if he knew

of them, he would not have made the investment. Instead, Carl cut out

one-foot squares of 5/8" plywood and nailed them into a stack 8"

high or so. My job, as Carl lowered the hammer cap, was to balance a plywood

stack on top of a pile and wrestle all three elements into line.

The worst that can happen, of course, is that the crane (or operator)

malfunctions, and the hammer comes down too fast or begins to sway. The

edge of the hammer will prune a man's hand off if he can't get it out

of the way. If the boom starts swinging, there's little one can do but

be ready at any moment to push backward off the pile with his feet, hoping

that when his momentum pulls him back toward the pile and the hammer he'll

not be caught between them. Carl was pretty steady, but one day, sinking

the foundation for a water tower in Arapahoe, down in Furnas county, Nebraska,

he somehow dropped the hammer while hoisting me up. It rushed past me

as free weight for maybe 6 or 7 feet, and when it stopped the cable stretched

tight, the back of the crane jerked up off the ground, the boom pitched,

and I shot up into the air. My own falling weight took the slack out of

my cable and the unpadded harness left deep bruises the way a seatbelt

might after an auto accident; somehow I avoided contact with the pile.

The more routine danger for a fly-man, however, involves the hammer catching

the edge of a plywood pad as it comes down. Before he can holler stop,

or muscle the pile into alignment, the full weight of the hammer might

pinch down on the very edge of a pad, spinning it off the top of the pile

like a ten-pound frisbee. This happened often enough that everyone working

below stopped and looked up when a pile is capped. When a pad jumps off

the top of a pile, the fly-man yells "Heads," and there’s

great joy in the hole below as the crew point and laugh at whoever has

to scramble out of the way. The fly-man—because the pile doesn't

spin into his face—usually laughs longest and hardest.

* * *

In

the spring of 1987 I am a college senior. Unlike Carl Andresson (who

used to flip us off with what was left of his severed

middle finger and

say he was only “half joking”), or the dispatcher at the

concrete plant (whose forearm was trimmed to the bone by the aggregate

conveyor before he dislocated his own elbow to reach the kill-switch),

I am able to type. It’s been four years since I fled construction

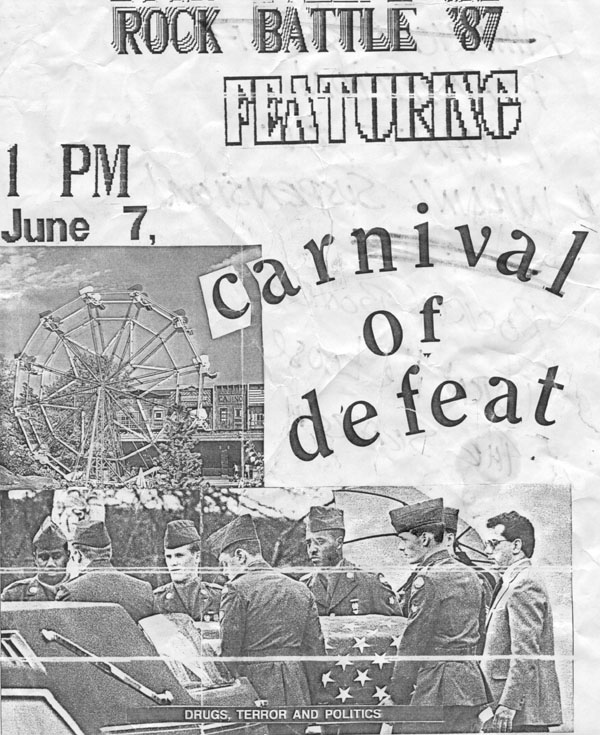

and went back to school. I've just turned 29. My most recent band, Carnival

of Defeat, broke up late that summer after winning a regional battle

of the bands and recording a five song demo that would have culminated

in my second record. I have already given up on starting

a new band, which is just like being in a relationship—without

the sex to smooth over disagreements. I turn all my attention to reading

literature and writing poetry. I don't think of school as a place I have

to go; I give myself willingly to it. I am back in the Reading Club.

That fall, I write an ironic poem for my workshop that juxtaposes graphic

and tragic world issues with the front-page preoccupation of that Sunday's

Omaha World Herald—the Nebraska Cornhuskers. The team has barely

survived an early season game, and the sophomore quarterback, Steve Taylor,

is tested—as it turns out, he can throw. My professor,

Don Welch, praises the poem in class, and encourages me to send it to

the school newspaper, which I do. It is published the following week,

in two different columns, rather obviously disrupting the poem's formal

character. The next issue carries a letter from a philosophy professor

who accuses the paper's editor of "breaking the back of Mr Vandenberg's

poem" and likens the incident to the new president's directive—some

weeks earlier—to alter the bas-relief on the school's bell tower

by sandblasting the testicles off some Roman horses. The professor declares

the school hostile to the humanities. I am suddenly caught up in a war

over the arts between the faculty and the Administration. It feels so

good.

Unsure of what else to do, I apply for a graduate assistantship. In December,

I go to the "new teacher's orientation," which is actually a chance

meeting outside the chair's office. He tells me who to ask about my course

schedule and that if any students give me any trouble whatsoever, to simply

delete them from the roster. I ask him about how and what to teach. His answer

implies that my course will be driven by the design of a textbook—he

tells me to go up and down the hall and "ask what others are using," or "use

what your own freshman English teacher used."

The following spring I spend a lot of time talking about thesis statements.

I assign readings from a shiny, silver handbook and lead students through exercises

asking them to identify parts of speech or correct the handbook author's planted

errors. I talk some more about thesis statements. I draw rectangles and triangles

on the board, and call them paragraphs. Then, I talk even more about thesis

statements and the geometric simplicity of a claim and three well-supported

reasons. I explain how the inverted triangle introduces the rectangles, and

each in turn elaborates one third of the triangle’s upside-down apex.

One day, in a very busy graduate-student office, I meet with a young woman

whose essay exposes the dangers of college softball. At the end of her triangle,

she has written, "College softball is dangerous because you can get hit

by the bat, hit by the ball, or spiked by cleats."

Geometrically, she is aces; but both of us sense a problem. Uncertain of the

implications, I apply a mimetic test, asking, "Women don't wear cleats

in college softball here, do they?"

"I had to have a 'third thing,'" she says.

* * *

Recently one of my graduate students in Multicultural Rhetorics and

I are scaling the stairs of McGaw Hall, going back to the classroom from

the pop machine. I'm interpreting many new teachers' impatience with

theoretical discourse, their intense pragmatism, their tendency to oppose "theory" to "practice." I'm

doing it this way:

The desire to “use theory,” to ask “How can I use this

in the classroom to solve problems?” is always well motivated—good

teachers want to do the best they can for their students. But it is also

part of the dominant ideology—teachers are called out to, interpellated,

solely as practitioners, and if all a teacher looks for is how to manage

the problems in front of her, she may not see (or seek to counter) the

hegemonic systems that create the problems she sees in front of her.

I think I'm making some headway, legitimizing as a kind of critical practice

the discourse of "Theory" that MA students often find smug,

obscure, irrelevant; we climb a whole flight without a word, and as I

open the third-floor hallway door, she says, "I wish I had that kind

of time."

I drain back into the classroom for the second half remembering Bordieu, my

best counter-hegemoic intentions reframed as an activity of the leisure class!

I tell my students with great irony what has just happened, throw up my palms,

and gesture to the African American student who just a week before painfully

asked of no one in particular, "when you see yourself being absorbed by

the very system you're trying to change, how do you avoid just hollering out

'FUCK'"?

We sit in silence for awhile and then, because we cannot do much else without

losing track of who our circumstances tell us we are, we turn back to the reading.

* * *

Put yourself in this position: You wake up on Friday morning, put on

a tie, and meet a class of college students. You're drawing a check from

the state as a teaching assistant, and you're a month or so from finishing

your MA in English. You think your job is opening students up to the world

of ideas. With them, you're reading Zen and the Art of Motorcycle

Maintenance. You talk about social epistemology, narratology, etceterology.

You talk about maintenance as a trope for self-reflection, self-examination.

You talk about Pirsig's trope for the University—"A Church

of Reason." You ask if one must be reverent and ironic about that

idea at the same time. You ask students to come up with their own metaphors

for the university. You grow impatient with their indifference. You remember

Ira Shor's book, Critical Teaching and Everyday Life, and you

ask if warehouse might be a possibility.

But the check from the state is not nearly big enough. When class is over,

you rush home, take off your tie, and pull on a pair of lined coveralls.

You drive out to your other job at Plaza 66 along the Interstate, grabbing

a Whopper on the way because they're 99 cents on Friday. (On Tuesday,

you stop at Taco Johns, because the tacos are two for 99.) Weekend travelers

are already draining off the freeway; it's going to be an "on"

weekend, which means like the weekend two weeks before and two weeks after,

you'll be here for nine hours on Saturday and thirteen hours on Sunday,

averaging forty hours a week like you have been for the last seven years—since

you left driving piles behind.

Maybe you're stealing another bite from the already cold Whopper when

Robert Allen pulls up at the full service island. He's a student in the

class you're teaching, and he's headed home to Omaha for the weekend with

three other students—all of them sitting stone faced. He tells you

to fill it up with premium, and that there should be 32 pounds in all

the tires. When you pull up off the deck, off your knees, he asks if you'd

mind checking the oil. You jerk up the hood, and as you lean over for

the stick you bend a little further than you need to—like dragging

your tongue over a canker sore, you can't resist taking a glance through

the gap between the hood and the engine compartment to see them grinning

at each other. It's a big four-door Ford, probably his father's "old"

car, and there is barely a drop of thin black oil hanging from the bottom

of the stick—probably two quarts low. You push the hood down against

the springs, maybe harder than you have to, and you tell him the oil is

“just fine.”

He hands you the Phillips Executive card with Robert Allen, Sr, on it,

and you complete the transaction. As he speeds off the lot and up the

road toward the ramp, you fantasize: maybe someplace later that afternoon,

east on I-80, say, between McCool Junction and Beaver Crossing, a tired,

dry rod will tear loose and begin spinning violently on the crank, goring

the pan open before the piston bounces off the head and shoots deep into

the block, seizing the engine.

Maybe later, you're fixing a tire, and a guy in a suit with New York plates

comes in and asks how you goddamn flatlanders like growing rich off him

as he has to travel across your sorry-ass state. You need the job, so

you don't say that only someone from New York could not guess that gas

would be a fifteen cents cheaper six blocks further into town. You smile

and say that you realize how miserable Nebraska is, that no one ever comes

back, that you have to get all their money at once.

When you're done in the shop, and the traffic slows down, you pull out

the copy of Jude the Obscure you're reading for a graduate class,

and lean against the back wall where you can see the owner if he pulls

up, but he can't see you. He's already explained that if he catches you

on your ass one more time with your nose in a book you're going to be

looking for work. He's caught you reading dozens of times in seven years,

and you know he won't fire you because you both know he won't easily find

someone else he can trust with three grand a day, for minimum wage, on

this schedule. You hide your reading to save him the humiliation of an

empty threat.

* * *

My brothers and sisters congregated at my parent's home for the final

time on Thanksgiving weekend of 1988. My parents were gone; we were there

to shape up the yard so the house could be sold. When my father built

the house in the early 1950s, the money he saved on construction went

into two lots. Over the years, the roads were paved and the neighborhood

filled in with ranches and split-levels, but no one for a block in any

direction had a house on a double lot. It was the place to play in the

neighborhood. Once, when my father poured a sidewalk, my mother took

a wheelbarrow full of concrete and a trowel, and made a grid of miniature

streets in a corner of the yard. Kids from all over would gather to roll

our O-scale vehicles around this little town.

My mother's landscaping had been untended for years; we cut down a sagging,

barren apple tree, and the few remaining poplars from along the fence line

in back. A long row of bridal wreath was dug out by the roots, and we pulled

down a large dog pen that my father had built for my sister's lab, Zorro, twenty

years earlier. As I was raking along the perimeter of the dog pen, I excavated

a Tootsietoy that I had played with in the yard as a kid—a 1947 Mack

L-Line tow truck that Tootsietoy produced between 1954 and 1966.

I took it in, washed it up a bit, and threw it in my car with some other things.

I didn't think much about it until a few years ago, when in an antique store

I bought the matching dump truck, which I also had as a child. I set out to

assemble my early Tootsietoy toy collection, and now can't stop. When we can,

Karen and I roam the countryside scouring antique stores for Tootsietoys. I

have around 210 of them manufactured between 1924 and 1988. Tootsietoy Internet

sites are bookmarked at home, and I of course have Tootsietoy books that recount

the history of the company, set benchmark values, and tell me which ones I

most desire.

* * *

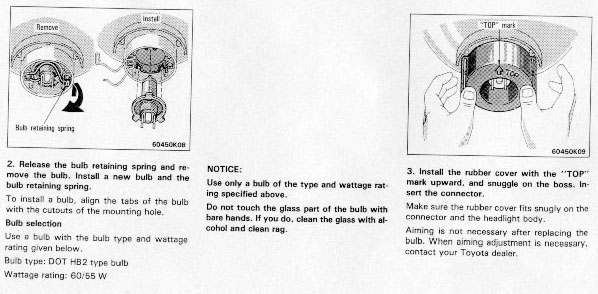

Last weekend, Karen tells me that one of the headlights on our aging

Toyota is out. We’ve planned to spend the next day on an antique

run, going south through Manteno, Mommence, Bradley, and Kankakee, Illinois.

It makes sense to me to stop somewhere along the way, pick up a bulb,

and pop it in out in the parking lot. I wait too long, and by the time

we get to the Kankakee Walmart, it is already dark and beginning to sleet.

I come out with the bulb, turn the car to take advantage of a big light

standard, and raise the hood. I open the cover plate over the light assembly

and unplug the lamp. I spin out a rubber grommet that is protecting the

leads protruding from the back of the bulb, but for some reason can't

dislodge the bulb itself. The overhead light will not illuminate the

headlamp enclosure, and I can't see anything. As any good natural-space

mechanic should, I began to berate and insult first the light, then the

part, and then the car in general—using the vocabulary I'd once

learned from John Newcombe.

Sweetly, Karen suggests we forget about it. "Let's just wait until we

get home; we'll pull it in the garage out of the wind; we'll have better light."

The one halogen is plenty safe enough for a freeway ride, and because

my brother Greg, who lives in another state, is the only state patrolman

who would get wet writing a ticket, I know the odds against being pulled

over are in my favor. We take off and an hour later I slip the car into

the garage and lower the door behind us. The garage isn't heated, but

out of the wind it doesn't seem cold. The light isn't as great as we thought

it would be. It never is.

Again I pop the hood and find the now familiar leads, attempting to spin the

bulb back out of the housing. It doesn't budge. I run my fingers over the back

of the bulb and the housing, comparing what I feel to the diagram on the back

of the package. Everything seems as if the bulb should simply spin out.

"Let me try," Karen says.

I move out of the way. Like I had, she tries

one hand and then the other. Nothing.

I walk around to the passenger side, open the glove box, pull out the manual,

and stand under the overhead light. Karen remains under the hood. The table

of contents directs me to "Maintenance— Electrical," and I

begin to read: "Release the bulb retaining spring and remove the bulb."

"Spring? That's not a spring," I moan, "There's a clip.

It swings across the back of the bulb like a gate."

"I've got it," she is already saying, and I hear the "spring" pop

loose and the bulb turn out of the housing.

And as Karen leans in under the hood of our car, reassembling the headlamp

housing, I stand there in the middle of my middle-class space, under a

dim, bare bulb, holding a book.